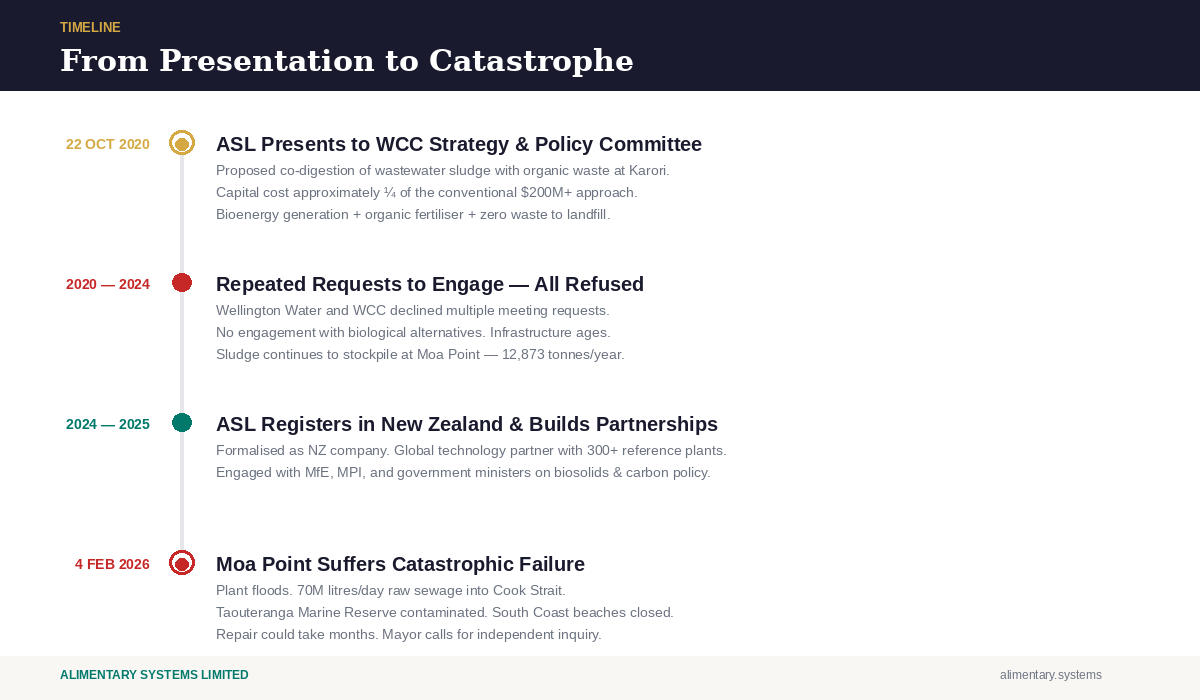

In October 2020, four months before Alimentary Systems was even registered as a New Zealand company, our founders presented a circular bioenergy solution to Wellington City Council. They chose not to engage. Five years later, the system collapsed.

On 4 February 2026, Wellington's Moa Point Wastewater Treatment Plant suffered what Mayor Andrew Little called a "catastrophic failure." The plant's lower floors flooded completely when sewage backed up in the 1.8km outfall pipe. Within hours, approximately 70 million litres of raw, untreated sewage per day was pouring directly into Cook Strait and across the capital's South Coast beaches.

The Department of Conservation described itself as "extremely concerned." DOC's principal marine science advisor, Shane Geange, warned that raw sewage carrying bacteria, viruses and parasites posed an immediate threat to sponges, mussels, fish, and the local penguin population. The Taouteranga Marine Reserve — just 2km from the discharge point — sits directly in the path of contamination. South Coast beaches were closed. Kaimoana collection was banned. The public was told to stay away.

Redirecting the overflow further out to sea could take months. Even once the longfall pipe is restored, Wellington Water acknowledged that raw sewage would still need to be periodically pumped near the shore because the temporary arrangement has limited capacity.

Water NZ CEO Gillian Blythe put the matter plainly: New Zealand needs regulatory oversight reform and sustained investment in water infrastructure.

None of this should have come as a surprise.

The Solution Was Offered Before ASL Even Existed in New Zealand

On 22 October 2020 — more than five years before this disaster, and four months before Alimentary Systems Limited was even incorporated as a New Zealand company — the founders of what would become ASL stood before the Wellington City Council Strategy & Policy Committee and presented a different path.

ASL did not yet exist. At the time we were not a registered company, we were a few people with deep domain expertise, a proven international technology partner, and a clear warning: Wellington's conventional approach to wastewater was unsustainable, and there was a circular alternative that could prevent exactly this kind of failure.

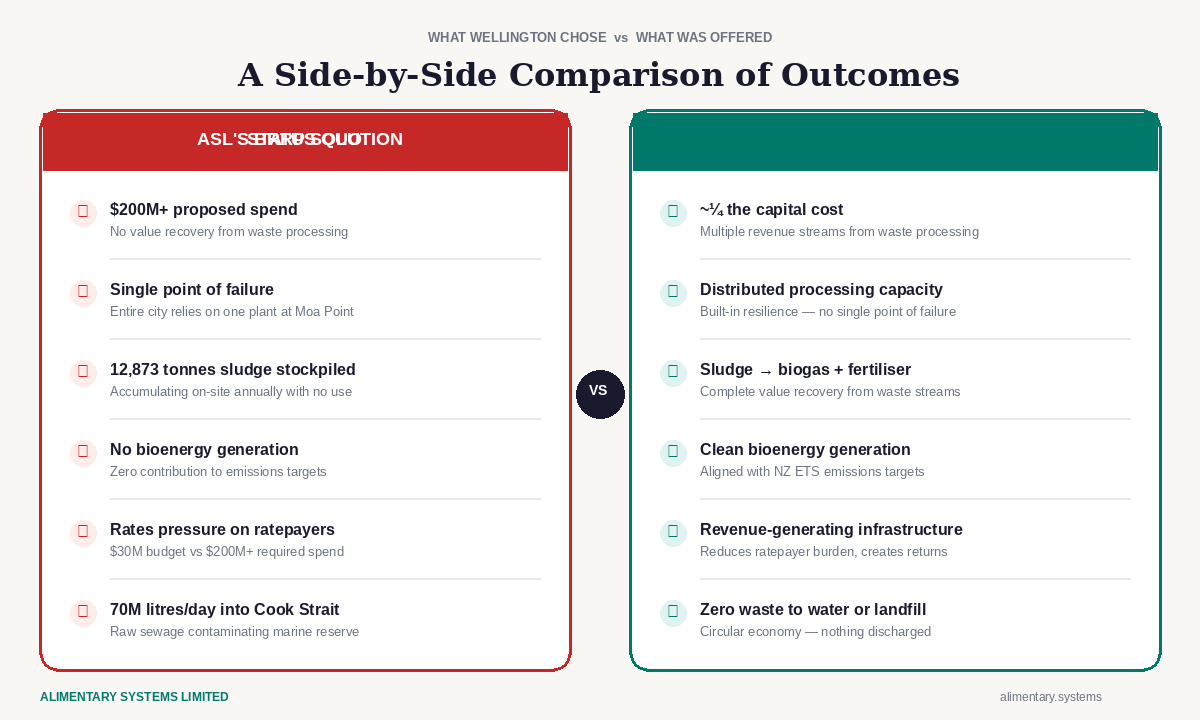

Our presentation outlined co-digestion of wastewater sludge with organic waste streams — food waste, green waste — to produce bioenergy and organic fertiliser. Rather than treating waste as a liability to be disposed of, we proposed treating it as a feedstock. The technology prevents wastewater sludge from being discharged to land or water, eliminates emissions from processing, and generates revenue from what would otherwise be a cost centre.

We didn't ask for a contract. We asked for a conversation — specifically, to discuss how a biological approach could work at Karori, processing 2–3 tonnes per day, at a capital cost approximately one quarter of what was being proposed through conventional methods.

Wellington's existing plans at the time would have cost the city over $200 million, against a rates budget of approximately $30 million, inevitably forcing rates upward. That proposal did not create bioenergy. It did not reduce waste to landfill to zero. It did not recover value from the waste streams it processed.

Had Wellington engaged with us then, ASL could have been established in New Zealand specifically to deliver that solution. Instead, we incorporated ASL on 10 February 2021 — without Wellington's involvement — and built the company from Christchurch.

The Door Was Closed Before We Could Even Open It

Despite our presentation to the Strategy & Policy Committee — delivered before ASL was even a registered entity — the operational stakeholders at Wellington Water and Wellington City Council refused repeated requests to meet. Biological approaches were overlooked. The conversation never happened.

This was not a failure of technology. It was a failure of engagement. The solution was on the table before the company behind it even formally existed in New Zealand.

Wellington's wastewater infrastructure has continued to age. Investment has lagged behind need. And on 4 February 2026, the consequences arrived — not as a slow decline, but as a catastrophic, immediate failure affecting public health, marine ecology, and the city's reputation.

The Numbers Tell the Story

Moa Point is Wellington's primary wastewater treatment facility. According to national WWTP data from 2019–2020, the plant processes approximately 25.6 million cubic metres of wastewater annually, serving a population of around 158,000. It produces roughly 12,873 tonnes of sludge per year — sludge that has been stockpiled on-site with no value recovery.

Wellington Water manages just two plants across the region, processing 27.3 million cubic metres per year combined. This concentrated infrastructure means that when a single point of failure occurs — as it did at Moa Point — the entire system collapses. There is no redundancy. There is no resilience.

ASL's Bioresource Recovery Plant (BRRP) technology is designed precisely for this context. Co-digestion creates distributed processing capacity. It diverts organic waste from landfill. It produces biogas for clean energy and fossil-free organic fertiliser. It reduces the volume and toxicity of sludge. And it does so while generating multiple revenue streams rather than consuming ratepayer funds.

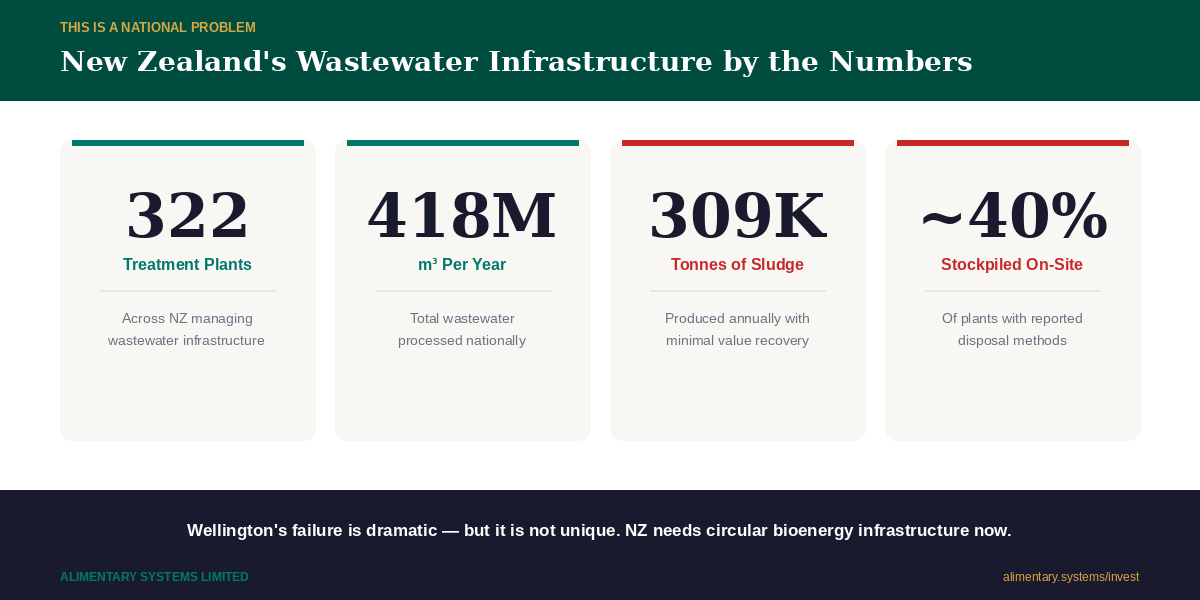

This Is a National Problem — And the Regulator Just Confirmed It

Wellington's failure is dramatic, but it is not unique. On 11 February 2026 — exactly one week after the Moa Point catastrophe — New Zealand's water regulator Taumata Arowai appeared before a select committee and painted a stark picture. Chief executive Allan Prangnell confirmed that approximately one third of New Zealand's 320 wastewater treatment plant consents have expired — some for as long as 20 years. He told MPs that the risk of another Moa Point happening elsewhere is currently unknown.

More than half of all wastewater overflows occurring around the country are not consented. Underground pipes — accounting for roughly 80 percent of the overall three waters network — are in many cases of unknown condition. As Prangnell put it: the picture is "murky."

Across New Zealand, 322 wastewater treatment plants manage 418 million cubic metres of wastewater annually, producing over 309,000 tonnes of sludge. Approximately 40% of plants with reported disposal methods stockpile sludge on-site. Another 30% send it to landfill. Only a fraction recover any value.

The infrastructure is ageing. Consents are expiring. Regulatory pressure is increasing. And as the NZ Emissions Trading Scheme tightens — with agricultural emissions pricing deferred until at least 2030 — the waste sector will be required to shoulder a greater share of New Zealand's emissions reductions.

The February 2026 letters between the Minister of Climate Change and the Climate Change Commission make this explicit: NZ ETS-covered sectors must deliver additional reductions. Domestic solutions are being prioritised. The policy environment has never been more favourable for circular bioenergy infrastructure.

What Could Have Been

Had Wellington engaged with us in October 2020 — when the company didn't even exist yet — ASL could have been formed with Wellington as a foundation partner. By now, the city could have had operational co-digestion capacity processing wastewater sludge alongside food and green waste. It could have had distributed processing reducing reliance on a single point of failure at Moa Point. It could have had biogas generation offsetting energy costs and contributing to emissions targets. It could have had organic fertiliser production replacing synthetic inputs. And it could have avoided the environmental disaster now unfolding across its South Coast.

Instead, 70 million litres of raw sewage per day is flowing into Cook Strait, threatening a marine reserve, closing beaches, and contaminating kaimoana gathering areas — in the middle of summer.

The Path Forward

In October 2020, we were two founders without a company. Today, ASL is an incorporated New Zealand company (registered 10 February 2021) with proven technology, a global reference base of over 300 plants through our partners, and active engagement with the Ministry for the Environment, the Ministry for Primary Industries, and government ministers on national policy relating to biosolids, carbon, and green fertiliser standards.

We have modelled the economics at scale. We have the technology. We have the regulatory alignment. What Wellington needed in 2020 — and what New Zealand needs now — is the willingness to listen.

The sewage is in the water. The question is whether we let it happen again.

Alimentary Systems Limited (ASL) is a Christchurch-based circular bioenergy company that designs and builds Bioresource Recovery Plants (BRRPs) to convert organic waste into clean energy and valuable byproducts. For investment enquiries, visit alimentary.systems/invest or contact us at 09 390 4564.

Sources:

- NZ Herald, "Screened wastewater now being discharged straight into Cook Strait," 5 February 2026

- Newstalk ZB, "Gillian Blythe: Water NZ CEO on the need to invest in water infrastructure," 6 February 2026

- RNZ, "DOC becoming 'extremely concerned' about Wellington sewage leak," 5 February 2026

- RNZ, "Fears of another Moa Point, as scale of wastewater plants problem revealed," 11 February 2026

- ASL Presentation to WCC Strategy & Policy Committee, 22 October 2020

- NZ Wastewater Treatment Plant Data, 2019–2020